The American Dream Reimagined at the Trump Tower Penthouse

At first, I set out to explore Nathalie Olah’s ‘Bad Taste’, a searing cultural criticism of the “politics of ugliness”1 wrapped in a glossy leopard print backing. 50 pages in, I was struck by the observation that “there’s a tendency to forgive extreme wealth” when “the psychological trappings” of interior design are “a little more sophisticated and complex”2 than meets the eye. Minimalism and its process of “erasure”3 is really just capital disguised in metaphorical wardrobes for America’s elite. “As if modest tastes could absolve someone of their place in an exploitative class system,”4 Olah says. However, I’d argue we’re seeing the opposite visually with Trump. Where the “blank face of minimalism” has become “the face of capital, the face of authority, the face of the father.”5 Whilst the president’s maximalist and in “bad taste” style reveals a more honest, emotive and aspirational expression of the American Dream today.

Focusing on the president’s penthouse at Trump Tower, I’ll unpack the significance of its break from the flattening effect of commercialised minimalism. In a context where wealth disparity is at its highest ever and the austere, neutral visual language of technology dominates and distracts from the economic, political and social realities of American life offline.

Trump Tower at 725 5th Avenue can be accessed through a pair of golden revolving doors. Inside, the all that glitters of more gold finishings and creamy pink marble encasing next to every surface is amplified by the “gurgling of a dramatic 80-ft waterfall as well as the voices of those who've come to gawk at the opulent decor and six floors of expensive shops".6 Henry Conversano, Trump’s original decorator and a pioneer of modern casino design described the vision as “abundance beyond need.”7 Extracting the marble required “a Carrara mountain peak to be removed”8 and Ivana Trump’s creative input was so selective that all slabs with large white veins were replaced. At the Tower’s opening in 1983, The New York Times described it as a “pleasant surprise” and “rare” that a “new building” should prioritise “materials and workmanship, as opposed to qualities of space and light.”9

Replacing the elementary qualities of minimalism, “space and light”, with the “materials and workmanship” of Trump’s “Haute Baroque Capitalism”10 or “Versailles Nouveau”11, established an aesthetic break from the surrounding skyscrapers. A builder by trade, Trump understood the power of a visually distinct edifice. Dejan Sudjic describes the interrelationship of human psychology and architecture as “seeking to shape the world…the first, and still one of the most powerful, forms of mass communication,”12 that can “glorify and magnify the individual autocrat and suppress the individual into the mass.”13 Fittingly, Trump told many a losing contestant to get from his “suite to the street”14 over the fourteen years of his reality TV show The Apprentice running on NBC.

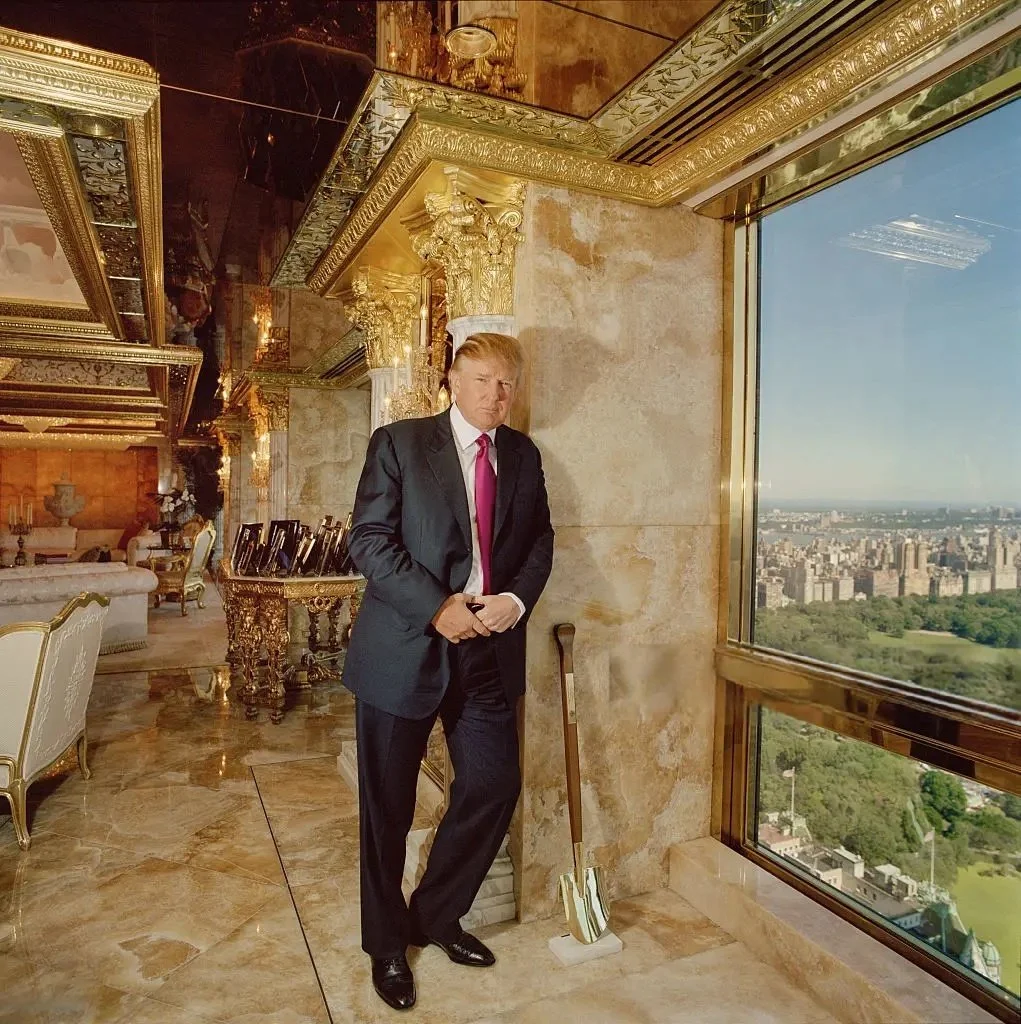

The penthouse apartment, Trump’s primary residence until 2019,15 occupies the top three of Trump Tower’s fifty-eight floors. Like the building, Trump’s home is largely inspired by large. In his autobiography, The Art of the Deal, Trump acknowledged that “while I can’t honestly say that I need an eighty-foot living room, I do get a kick out of having one.”16 Bar the bedroom (there are no images of it available online), a living room is perhaps the most revealing space to gage how one sees, and wants to be seen, living. Trump’s decoration style has been shrewdly defined as “Baroque Capitalist.”17, a reimagining of the exuberant 17th-century design movement most associated with the overt opulence of the pre-revolutionary French royal courts. Mythological frescos of what appear to be gods with fire torches, spears and shields all sit cushioned on clouds held up by stocky marble columns with ornate layers of cornicing. Two bulbous crystal chandeliers demarcate key sections of the living room ceiling and allow for a perfect symmetry in close to all the furniture that falls beneath them.

The floors are a gleaming creamy marble with generously zoned carpeting in an equally creamy pale pink silk-blend to match the roomy silk sofas. All this creamy soft furnishing sets the stage for the lashings and lashings of gold that lick nearly every surface from column tops, walls, windows, chairs, tables, mirrors, candelabras, pillow pom poms, bowls of Lindt chocolate balls and most interestingly, a gold spade displayed on a plinth. An object seemingly more sentimental than most as Trump chose to pose next to it for the photograph (below).

The images mythologises Trump as a worker — living amongst the grandeur he still gravitates towards his humble, handheld instrument for a portrait. The message is clear: if you dig hard enough, you will find enough gold to coat everything from your spade to your tower. The gilded living room is the semiotic American Dream. A dream first coined by historian James Truslow Adams as “a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone.”18 Indeed, the range of objects — from golden pillars to shovels — materialises that possibility for “everyone” to be “richer” and “fuller”.

Given America has the largest wealth disparity between rich and poor than any other developed nation — the culmination of over sixty years of rising inequality — Trump, the “Baron of Bad Taste”19, is confirmation that economic capital is now urgent where cultural capital is irrelevant. According to journalist Kyle Chakya in his cultural critique of the commercialisation and commodification of American minimalism Longing For Less, “(throughout) the 20th century, material accumulation and stability made sense as forms of security” but “little of this feels true today.” Tangible goods now cost exceedingly less, and intangible “forms of security” cost exceedingly more,20 which illuminates the attraction of the ostentatiousness of Trump’s material language.

Identifying with an aesthetic that communicates capital is a defiant reclamation and visual reassertion of a resource available to self-express. While “intangible” value might have contributed to the flattening and homogenisation of visual culture. After all, “unlike some other cultures that resent the rich or the upper class, Americans admire wealth.”21 Which supports the fact its not just poor and disgruntled Americans resonating with Trump. In a UBS survey of 971 U.S. investors, the majority saw Trump as better equipped to deal with the economy and taxes (51% and 52% respectively.)22 And so, Trump’s style, with its signalling of conspicuous consumption, is seen to be innately entwined in the American identity.

If the fundamental difference between “bad” and “good taste” is that to be bad is to be brash, indiscreet and over-designed, to be good is to be sparingly selective with careful consideration paid to quality materials and omitting a valued message of “fetishised restrained elegance.”23 Minimalism, as it pertains to the “elites” Trump has railed and rallied his support against, follows the creative maxim that “the archetype of all taste, refers directly back to the oldest and deepest experiences, those which determine and over-determine the primitive oppositions— bitter/sweet, flavourful/insipid/cold, coarse/delicate, austere/bright — which are as essential to gastronomic commentary as to the refined appreciation of aesthetes.”24

The notion of contrast as essential to “the refined appreciation of aesthetes” perhaps underpins American minimalism. Where well-off people tastefully contrast themselves with minimal, sparse living environments to offset their economic influence. Hoping the aesthetic intention of humility will, like Olah said, “absolve (them) of their place in an exploitative class system.”25

In The Longing For Less Chayka identifies the “strategy of avoidance” in minimalism, “especially when society feels chaotic or catastrophic.” The philosophy of “less is more” becomes a “coping mechanism for those who want to fix or improve the status quo instead of overturning it.”26 This has mutated minimalism’s purist principles and concept of restraint into an “aesthetic language through which to assert a form of walled-off luxury—a self-centred and competitive impulse that is not so different from the acquisitive attitude it purports to reject.”27

What better place to see minimalism’s limitations play out than the White House, America’s nuclear home. The building was designed in reaction to the imperialist tropes of European architecture to project “a message of simplicity, democracy and egalitarianism.”28 Pre-Trump, candidates typically tried to tamp down the perception of wealth. “Lyndon Johnson, of all people” was conscious of what his design style said about him. “Speaking of his own White House interiors, LBJ drawled “Every time someone calls it a château, I lose 50,000 votes in Texas.”29 while Franklin Delano and Eleanor Roosevelt emphasised rusticity, waxing eloquently to reporters about his tree farm and her artisan furniture in upstate New York. A previous billionaire candidate, Ross Perot, packaged himself as “Texarkana folksy” while Mitt Romney backpedalled after being mocked during the 2012 campaign over plans to install an elevator for his cars in the garage of his oceanfront home in La Jolla, California.30

Unlike the dictators and despots or European homes of democracy like the Elysée Palace, paradoxically filled with gilded 18th-century furniture, the White House was the architectural reimagining of what democracy could be, even if it's fallen short at just an architectural definition. Indeed, as far back as 1954 the American critic Russell Lynes said of modernism, the father of minimalism, that its persistent popularity appealed to the American psyche for its “harking back to American puritanism, a morality which stressed the virtues of modesty, clean living, and disdain for what we call vulgar display.”31 Concretising this shift is one of the last executive orders of Trump’s first presidential term to “Make Federal Buildings Beautiful Again”32 in the style of “Ancient Greek and Roman public buildings…the Middle Ages and the Renaissance”33, words taken directly from the White House’s order, pning for a time where absolute power ruled supreme. The order was met with the response of over 11,000 letters to the White House from American architects, an official condemnation from the American Institute of Architects and wider public outrage.34 The order was never signed.

The best place to analyse the irreconcilability of American minimalism today and its economic and socio-political reality is the technology industry. Home to the most billionaires in the world and a key architect of the economic disparity in the US. Technocracy is a reality that’s now unable to be contained by even the most severe and functional expressions of minimalism’s visual language like that of Apple, the world's largest technology company.

Apple’s look captures the apex of commercialised minimalism. Its design ethos follows the saying that: “good design is as little design as possible.”35 With products ever-evolving to be “thinner, lighter, and smoother than the last.”36 Its “machines are becoming infinitely thin, infinitely wide screens that we will eventually control by thought alone because touch would be too dirty, too analog.”37 But that illusionary simplicity is deceiving. By capturing just the “bare essentials” in its design, Apple works to largely elevate those few materials we engage with whilst eradicating the very tactile, messy reality of their creation. For example, “the Cloud’s” storage is grounded in the less than attractive reality of giant “server farms absorbing massive amounts of electricity” or there’s the “Chinese factories where workers die by suicide or devastated mud pit mines that produce tin.”38 It’s what Chakya called the reliance on a hidden “maximalist assemblage”39 that conversely, Baroque Capitalism thrives off, being a style characterised by its own excess, dynamism, and flamboyance. Altogether, it makes Trump’s aesthetic “very definitely a culture of feeling”40 while technology is austere and sleekly self-conscious, inviting those engaging with it to disappear into its restrained interface. Seeing Trump’s taste as a reaction to the apathy of technology can be contextualised by Professor Sugandha Gumber who observed that “in this digital age, machines were developed to speed up and simplify work”41 but instead we’re seeing that they have “added multiple layers of complexity to our lives” despite the veneer of simplicity.42

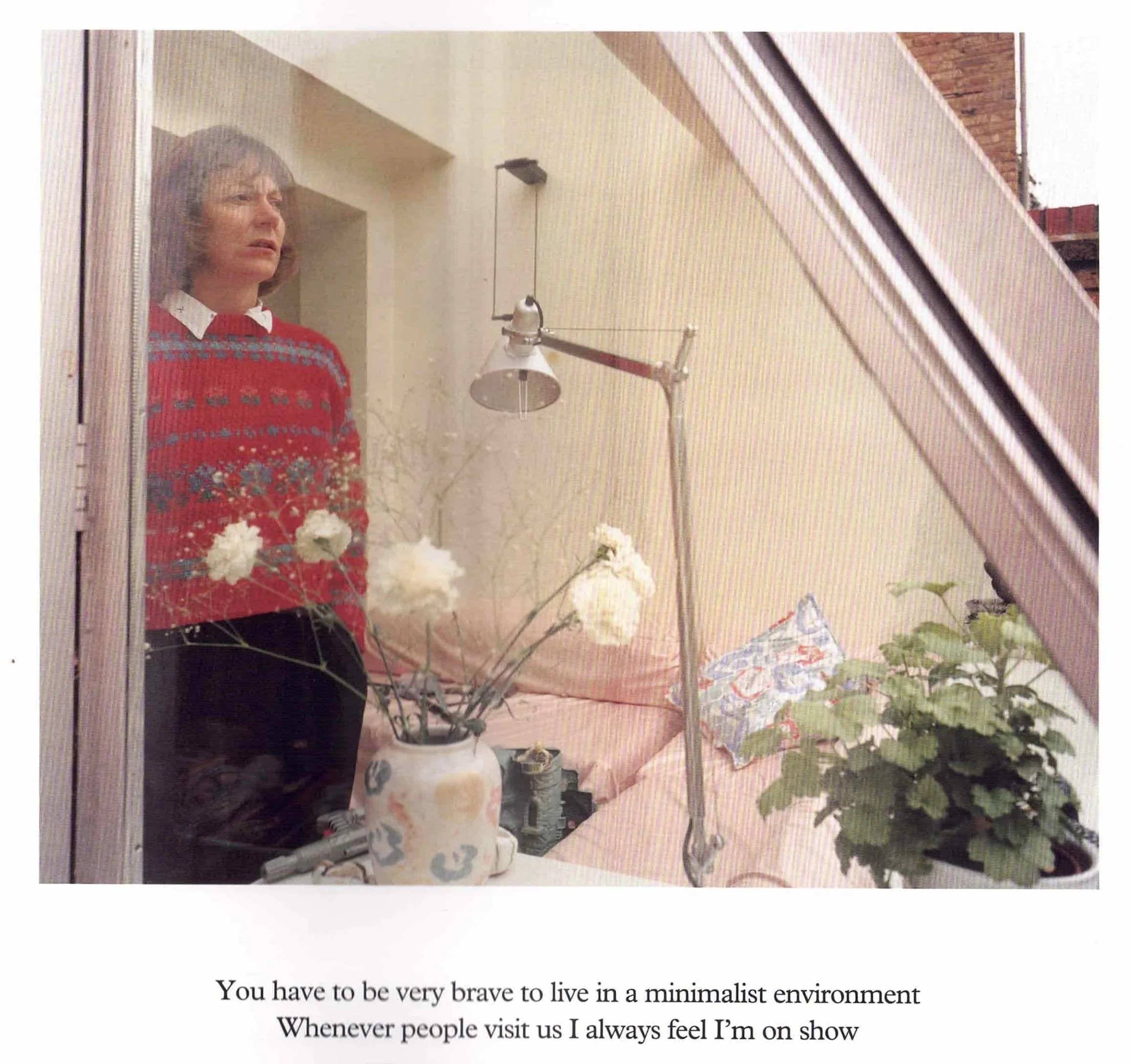

To compare these vastly different design styles semiotically, materials are the most elementary way of seeing and drawing out their ideological differences. In minimalism, glass, steel symmetry and endless expansive white walls communicate a message of purity and openness. Letting the outside in humbles one to the greater elements. It’s also incredibly revealing, “you have to be very brave to live in a minimalist environment. Whenever people visit us I always feel I’m on show” said a homeowner in Martin Parr’s 1991 photographic series A Sign of the Times: A Portrait of the Nation’s Tastes.43 But there’s also an irony to the “invisible” nature of glass best seen at the many edifices neighbouring Trump Tower. Where a quarter of a million migrating birds die each year hurtling into the “invisible” buildings that make up New York’s skyline. Trump Tower may be one of the rare few thats refusal to be invisible prevents it from the misleading consequences of an illusive ideology: “stripped of the traditional signs of status and ostentatious, wealth looked modern” Deyan Sudjic said of the modern skyscraper.44 Gold, marble and the theatrical and flamboyant qualities of Trump’s Baroque Capitalism are in their essence, transparent. Communicating a straightforward display of power and a penchant for luxury. Since Antiquity, the high cost and unearthly quality of gold gave the material associations with royalty and their gods. To eat, sleep and shovel like Trump with gold coats the quotidian with a material that after the French Revolution became symbolic of an “absolute power”45 “frozen in time”46 whilst democracy seemed to move on without it.

But if minimalism can now be understood as too simple “a way of dealing with (the) complexity”47 of democratic life, perhaps then it ushered in Trump’s Baroque Capitalism. “We are now post-truth, so we may also be post-taste”48 The Spectator wryly noted. If Trump is holding up “the cultural mirror to what we wish to reject or outgrow”49 perhaps we’re better off embracing and integrating the more abrasively Trumpian qualities of the American Dream at a time when it feels harder and harder to achieve and so, more and more necessary to reimagine. Replacing the neutrality of greige, beige, glass and steel with a sea of red MAGA caps at a Trump rally or star-studded “Never Surrender” gold trainers - Trump’s now sold-out merch. To cultivate a “leap away from the homogeneous looks that have dominated visual culture for a decade.”50

In 2016, the German historian and political philosopher Jan-Werner Müller “offered a new definition of the term populism proposing that populist leaders are defined less by anti-élitist rhetoric than they are by their insistence that they represent an unheard majority of the people.”51 And Trump with his “rivetingly tacky”52 “bad taste” and the media attention paid to his burgers, MAGA caps, fake Renoirs and fumbling of white-tie has successfully reappropriated the favourite put-down of New York decorators and their clients: “bridge and tunnel” — meaning the suburban outsider.53 Bolstering this “otherness” to a proud reclamation of even the very word populism typically rejects: elite. Politico said, “he and his voters are now the elite, the new elite, “the super-elite.” “Just remember that,” he said in West Virginia toward the end of the summer, “you are the elite. They’re not the elite.”54

And so, Trump compounds the irrelevance of a connection between good taste and good leadership. The Washington Post crystallised the association: “Trump must be a man who doesn’t bother with the details, doesn’t avail himself of ready expertise, who refuses to be a student of history or even of Google. White-tie attire is more science than art.”55

We see this back at the apartment where Historian Robert Wellington said Trump’s oversight on the formalities of Baroque’s accurate recreation and the absence of antiques suggests a desire to “create a fantasy of luxury and decadence; an imagined world that hints to Royal riches” while “accurate quotation”, “consonance” and a “refined understanding” become irrelevant.56 Indeed, it's the “very fact that elites reject Trump’s taste” that resonates, “people don’t want to be told by others that they’re in some way inferior”57 and Trump is celebrated precisely because he “eschews mainstream consensus on what is tasteful, permissible and stylish.”58

It would be bold to say that Trump’s design style equated to two presidencies. Although there is reason to believe it massively contributed given we live in such a largely image-driven society. Ultimately, the reality of the American Dream is irreconcilable with the design language of American modernism and minimalism. So Baroque Capitalism’s very ‘of this world’ visual language resonates - think the digging of gold or quarrying of marble - when American jobs and aesthetics are moving more and more online and subsequently further and further apart. Altogether, the Trumpian look offers the American Dream a tangible, hopeful and embellished alternative. While I’m not convinced Trump will ‘Make America Great Again’ perhaps he’ll ‘Make American Architecture and Interiors Honest Again’.

Trump poses next to a golden shovel displayed on a plinth at his penthouse apartment in Trump

President Johnson’s Oval Office, circa 1964. Photographer Unknown via the White House Historical Association

Excerpt from “Signs of The Times” by Martin Parr, exploring British decorative taste in the 1990’s. Book via the Martin Parr Foundation

(Right) Model of Philip Johnson’s Glass House, Connecticut, circa 1947. Via MoMA

(Left) The hallway of Kim Kardashian’s Calabassas home, designed by Axel Vervoodt and Vincent Van Duysen. Praised for its monasterial and purist design style. Photo: still from Vogue’s “Inside Kim Kardashian’s Home Filled With Wonderful Objects”, via YouTube

Mr. Trump looks out on a sea of red hats during a MAGA rally in Indiana in 2018. Photo: Doug Mills for the New York Times. From the article “What Does the MAGA Hat Mean Now?” November, 2020.

Steve Jobs sits at his home in Woodside, California, 1982. Photo: Diana Walker via La Razon

Donald Trump on top of Trump Tower, 1987. Photo: Harry Benson via Getty Images

The Penthouse Hallway at Trump Tower. Photo: Sam Horine via Getty Images

1 Olah, Nathalie. Bad Taste: Or the Politics of Ugliness. Dialogue Books, 2023.

2 Olah, Nathalie. Bad Taste: Or the Politics of Ugliness. Dialogue Books, 2023.

3 Olah, Nathalie. Bad Taste: Or the Politics of Ugliness. Dialogue Books, 2023.

4 Olah, Nathalie. Bad Taste: Or the Politics of Ugliness. Dialogue Books, 2023.

5 Chave, Anna. C. “Minimalism and the Rhetoric of Power”. Arts Magazine, Volume 64 No.5, Jan. 1990. http://annachave.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Minimalism.pdf

6 The Week Staff. “Inside Trump Tower: Donald Trump’s Manhattan high rise”. The Week, 15 Nov. 2016. https://theweek.com/78402/inside-trump-tower-donald-trumps-manhattan-high-rise

7 Leigh Brown, Patricia. “Lavish Luxuries: The Costs of True Luxe”. The New York Times, 12 Apr. 1987.

8 Bayley, Stephen. “Making America Crass Again, The man’s taste is as revealing as any of his outbursts”. The Spectator, 10 Dec. 2016.

9 Goldberger, Paul. “Architecture: Atrium of Trump Tower Is a Pleasant Surprise”. The New York Times, 4 Apr. 1983. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1983/04/04/076387.html?pageNumber=45

10 Shorin, Toby. “Haute Baroque Capitalism”. Subpixel Space, 11 Apr. 2017. https://subpixel.space/entries/haute-baroque-capitalism/

11 Leigh Brown, Patricia. “How Will Trump Redecorate the White House?”. The New York Times, 17 Mar. 2016.

12 Sudjic, Deyan. The Edifice Complex, How the Rich and Powerful Shape the World. Penguin Books, 2006.

13 Sudjic, Deyan. The Edifice Complex, How the Rich and Powerful Shape the World. Penguin Books, 2006.

14 F. Miller, Kristine. “Trump Tower and the Aesthetics of Largesse”. Designs on the Public, The Private Lives of New York’s Public Spaces, University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

15 Haberman, Maggie. “Trump, Lifelong New Yorker, Declares Himself a Resident of Florida”. The New York Times, 31 Oct. 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/31/us/politics/trump-new-york-florida-primary-residence.html

16 Schwartz, Tony and Trump, Donald. Trump: The Art of The Deal. Ballantine Books, 2015.

17 Shorin, Toby. “Haute Baroque Capitalism”, Subpixel Space, 11 Apr. 2017. https://subpixel.space/entries/haute-baroque-capitalism/

18 Leonhardt, David. “The American Dream, Quantified at Last”. The New York Times, 8 Dec, 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/08/opinion/the-american-dream-quantified-at-last.html

19 Bray, Catherine. “John Waters: ‘Trump ruined bad taste - he was the nail in the coffin’. The Guardian, 4 Jun. 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2022/jun/04/john-waters-trump-ruined-bad-taste-liarmouth

20 Szalai, Jennifer. “‘The Longing for Less’ Gets at the Big Appeal of Minimalism”. The New York Times, 21 Jan. 2020 https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/21/books/review-longing-for-less-minimalism-kyle-chayka.html

21 White, Gillian B. “Getting to the Bottom of Americans' Fascination With Wealth”. The Atlantic, 16 May. 2016. https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/05/greenfield-generation-wealth/526683/23

22 Their, Jane. “Most multimillionaire investors are voting for Harris, despite thinking Trump is better for the economy”. Fortune. 30 Sept. 2024. https://fortune.com/2024/09/30/millionaire-investors-ubs-survey-kamala-harris-donald-trump-2024-electio n/

23 York, Peter. “Rivetingly tacky, the Donald’s flat in Manhattan has style touches beloved by Middle Eastern despots”. The Sunday Times. 3 Apr. 2016. https://www.thetimes.com/life-style/property-home/article/how-to-live-like-donald-trump-rqv265qcd

24 Bourdieu, Pierre. Distinction, A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Routledge Kegan & Paul,1984.

25 Olah, Nathalie. Bad Taste: Or the Politics of Ugliness. Dialogue Books, 2023.

26 Chakya, Kyle. Longing for Less, Living with Minimalism. Bloomsbury, 2020.

27 Tolentino, Jina. “The Pitfalls and the Potential of the New Minimalism”. The New Yorker, 27 Jan. 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/02/03/the-pitfalls-and-the-potential-of-the-new-minimalism

28 York, Peter. “Trump’s Dictator chic”. Politico, 11 Mar. 2017. https://www.politico.eu/article/trumps-dictator-chic/

29 Bayley, Stephen. “Making America Crass Again, The man’s taste is as revealing as any of his outbursts”. The Spectator, 10 Dec. 2016. https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/making-america-crass-again/

30 Leigh Brown, Patricia. “How Will Trump Redecorate the White House?” The New York Times, 17 Mar. 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/20/opinion/sunday/how-will-trump-redecorate-the-white-house.htm

31 Lynes, Russell. The Tastemakers, Dover Publications, 1981.

32 Capps, Kriston. “Trump’s Defeat Didn’t Stop His ‘Ban’ on Modern Architecture”. Bloomberg UK, 12 Nov. 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-11-12/how-trump-s-modern-architecture-ban-could-live-on

33 Trump, J. Donald. “Executive Orders on Promoting Beautiful Federal Civic Architecture”. Executive Order, Trump White House Archives, 21 Dec. 2020. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/presidential-actions/executive-order-promoting-beautiful-federal-civi c-architecture/

34 Capps, Kriston. “Trump’s Defeat Didn’t Stop His ‘Ban’ on Modern Architecture”. Bloomberg UK, 12 Nov. 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-11-12/how-trump-s-modern-architecture-ban-could-live-on

35 Chakya, Kyle. Longing for Less, Living with Minimalism, Bloomsbury, 2020.

36 Chakya, Kyle. Longing for Less, Living with Minimalism, Bloomsbury, 2020.

37 Chakya, Kyle. Longing for Less, Living with Minimalism, Bloomsbury, 2020.

38 Tolentino, Jina. “The Pitfalls and the Potential of the New Minimalism”. The New Yorker. 27 Jan. 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/02/03/the-pitfalls-and-the-potential-of-the-new-minimalism

39 Chakya, Kyle. Longing for Less, Living with Minimalism. Bloomsbury, 2020.

40 Bragg, Melvyn. “The Baroque Movement”. In Our Time. BBC Radio 4. 20 Nov. 2008. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00fhp85

41 Gumber, Dr Sugandha. Minimalism in Design: A Trend of Simplicity in Complexity. ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing Arts, Oct. 2023.

42 Gumber, Dr Sugandha. Minimalism in Design: A Trend of Simplicity in Complexity. ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing Arts, Oct. 2023.

43 Parr, Martin. Signs of the Times: A Portrait of the Nation’s Tastes. Cornerhouse Publications, 1999.

44 Sudjic, Deyan. The Edifice Complex, How the Rich and Powerful Shape the World. Penguin Books, 2006.

45 Chrisman-Campbell, Kimberley. “How Gold Went From Godly to Gaudy”. The Atlantic, 2 Dec. 2016. https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2016/12/the-midas-touch-gold-trump-gouthiere/509036 /

46 Chrisman-Campbell, Kimberley. “How Gold Went From Godly to Gaudy”. The Atlantic, 2 Dec. 2016. https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2016/12/the-midas-touch-gold-trump-gouthiere/509036 /

47 Gumber, Dr Sugandha. Minimalism in Design: A Trend of Simplicity in Complexity. ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing Arts, Oct. 2023.

48 Bayley, Stephen. “Making America Crass Again, The man’s taste is as revealing as any of his outbursts”. The Spectator, 10 Dec. 2016.

49 Greindl, Marie. “What Exactly is Bad Taste?”. The Courtauldian. 5 Dec. 2024. https://www.courtauldian.com/single-post/what-exactly-is-bad-taste

50 Marriott, Hannah. “Dressing Pretty is over: this is fashion’s ugly decade.” The Guardian, 25 Jun. 2024. https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/article/2024/jun/25/ugly-fashion-trending

51 Chotiner, Isaac. “Redefining Populism, A political philosopher offers a new way of looking at Donald Trump, Narendra Modi, Jair Bolsonaro, and other right-wing leaders”. The New Yorker, 9 July. 2021. https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/redefining-populism

52 York, Peter. “Rivetingly tacky, the Donald’s flat in Manhattan has style touches beloved by Middle Eastern despots”. The Sunday Times, 3 Apr. 2016. https://www.thetimes.com/life-style/property-home/article/how-to-live-like-donald-trump-rqv265qcd

53 York, Peter. “Rivetingly tacky, the Donald’s flat in Manhattan has style touches beloved by Middle Eastern despots”. The Sunday Times, 3 Apr. 2016. https://www.thetimes.com/life-style/property-home/article/how-to-live-like-donald-trump-rqv265qcd

54 Kruse, Michael. “Trump Reclaims the Word ‘Elite’ With Vengeful Pride”. Politico Magazine, Nov. 2018. https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2018/11/01/donald-trump-elite-trumpology-221953/

55 Givhan, Robin. “Trump’s catastrophic fashion choices in England were not just a sign of bad taste”. The Washington Post, 5 June. 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/trumps-botched-fashion-choices-for-his-england-visit-are-n ot-just-about-the-clothes/2019/06/05/f86d19e8-87a7-11e9-a491-25df61c78dc4_story.html

56 Wellington, Robert. “American Versailles: From the Gilded Age to Generation Wealth”. The Versailles Effect, Object, Lives, and Afterlives of the Domain, Bloomsbury, 2020.

57 Leigh Brown, Patricia. “How Will Trump Redecorate the White House?” The New York Times, 17 Mar. 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/20/opinion/sunday/how-will-trump-redecorate-the-white-house.html

58 Birchall, Clare. “Haute Baroque Bling Style, Taste, Distinction and Populist Conspiracismin Distinction.” Populism and Conspiracy Theory, Routledge, 1 July. 2024.