Whilst self-exiled in Paris avoiding murder charges1, Eldridge Cleaver, former Minister of Information for the Black Panther Party, was on a mission to revolutionise men’s fashion and American minds.“Clothing is an extension of the fig leaf,” he declared, “it puts our sex inside our bodies. My pants, put sex back where it should be.''2

The “Cleaver Sleeves”3 debuted on Eldridge Cleaver’s return to California in 1975. They are trousers crafted from maroon denim with an adjoining pouch in the same fabric for the male sex organ to sit exterior, no longer tucked inside. Observing them, they propose at once a visual link and break from the then-American staple of jeans. A garment that had steadily been building momentum through the 1950s and 1960s, and was by now the most ubiquitous in the world. Synonymous with the unisex movement Cleaver was making his “direct attack” on.4

In this essay, I’ll unpick Eldridge Cleaver’s scorned attempt to reintroduce and recontextualise the codpiece in 1970s America. One of the many “deliciously contradictory”5 moments in his life. I will draw on Cleaver’s politics, the politics of a Black American male body and how the popularity of the codpiece in 15th to 17th century Europe contextualises all this.

Design Historian Judy Attfield said, “we use material things like dress to come to terms with our own bodies”6 Likewise, the codpiece mutated itself around the immutable to reflect the dominant ideologies of masculinity from the 15th to the beginning of the 17th century. Evolving from a baggy cloth with the simple task of sanitation and concealment to padded, velvety and pearl-encrusted. Complete with “ribbons and bibbons and all other sorts of nonsense.”7 Extending itself (literally) to functions as vast-ranging as a pincushion, fertility talisman, pistol or looking glass holder. Even somewhere to hang one’s spectacles or store a snack.8

According to professors Jean Howard and Phyllis Rackin in Engendering a Nation, masculine “identity” had shifted post-Renaissance from one defined by “patrilineal inheritance” to an “emergent culture” of “performative masculinity” secured through the sexual “conquest” of women,”9 replacing the “regime of the scrotum” and its “modest codpieces of the late fifteenth century” with “the regime of the penis”10 that ushered in “distinctly phallic”11 styles in “the shape of a permanent erection.”12

Eldridge Cleaver’s jeans are similarly entirely phallic. With no fabric allotted for the scrotum, they align themselves with “the regime of the penis” that emphasised “sexuality and especially phallic penetration.”13 Likewise, Cleaver’s foray into fashion was funded by royalties from Soul On Ice, his searing collection of essays written in solitary confinement during a near-decade sentence for rape and assault charges at Folsom Prison. In one of the book’s most chilling passages, Cleaver reflects that, ''rape was an insurrectionary act. It delighted me that I was defying and trampling upon the white man's law, upon his system of values, and that I was defiling his women — and this point, I believe, was the most satisfying to me because I was very resentful over the historical fact of how the white man has used the Black woman. I felt I was getting revenge.''14 Yet he continues self-critically, “I was wrong, I had gone astray — astray not so much from the white man's law as from being human, civilised — for I could not approve the act of rape.”15

Can we understand Cleaver’s jeans as him grappling with and giving material language to his own history of misogyny and sexual violence? Reimagining the medium of clothing to facilitate a redemptive honesty, where no longer hiding “it” allowed Cleaver to, at least sartorially, simplify the complexities of his desires and motivations. “We are a very sick country,” he said, “I, perhaps, am sicker than most.”16

At Harvard University in 1975, Cleaver was quizzed on the provocativeness of his design by undergraduates. "I'm really amused by the way people react to these pants” he said, “people who talk radical, about politics, then start talking conservative about these pants. What's wrong with getting an erection and letting people know about it? If a girl turns you on, why not let her know about it? There have been so many games going on between men and women for so long, that when sexuality finally comes out, it takes some pretty weird forms."17

Cleaver’s exhibitionistic philosophy links to the work of the largely misunderstood 18th-century French writer Marquis de Sade who, in the context of a stiflingly Roman Catholic France, had the “dogged determination to tell the truth about the human condition, a truth he located, not in soul or spirit, but simply, scandalously, in the sexual body, which for him was the only reality.”18 Despite their mutual perversions, Cleaver and Sade saw their commitment to challenging the confinement of sex with its often nastier, shameful parts to the interior world as regressive. A way of avoiding, in Cleaver’s own words, the “pretty weird forms”19 sex took when pressed down into the material metaphor of jeans. Interestingly, the majority of both Cleaver and Sade’s respective writings happened whilst they were both in solitary confinement for their respective sex crimes.

But is looking at the Cleaver Sleeves as an unconventional sexual revolution just an obfuscation of the real horrors and responsibilities of rape? In Cleaver’s New York Times obituary, Charles Johnson wrote that “private demons, even pathologies like those suffered by a serial rapist, can be camouflaged by the rhetoric of revolution during moments of social upheaval and, for a brief time, deceive us all.”20 But, Cleaver’s biographer Justin Gifford has a more sympathetic take, believing Cleaver’s sexual politics were underpinned by the perverse logic of becoming and in so, reclaiming the sexual violence attributed to him by “the white man’s law.”21 Nicknamed “Papa Rage” by other Black Panther Party members,22 Cleaver was furious to learn about the lynching of Emmett Till and the wider history of lynchings in America from prison at Soledad in 1955. Understanding that the majority of lynchings originated in a “fear of black male sexuality”23 with an often “phallocentric method” of aggression centred on the sexual organ,24 helped Cleaver contextualise the culture of “fear” which “restricted the gaze of Black men insofar as they had to be wary of accusations as severe as ‘eyeball rape’.”25

When Eldridge Cleaver was released from prison in 1966, anti-miscegenation laws were still in effect in most US states. They remained until 1967 — except in Alabama, which did not legalise interracial marriage until 2000. In 1969, a year after Cleaver fled the US, Pennsylvania passed a law imposing “the penalty of castration for a black man who attempted rape of a white woman and the death sentence for a black man convicted of the rape of a white woman.” While white men who committed the same offence would receive either a fine, whipping or one-year imprisonment.26 Illustrating the very incriminating reality of inhabiting a Black male body in America.

This “phallocentric” obsession with, and violence towards, Black American male bodies can be traced back to the first and founding sites of their mythologisation: slave auctions. Here, bodies were often displayed naked27 with “black male gonads…placed on a pedestal as an idol worthy of admiration and revile.”28 To be at once “admired” and “reviled” would have certainly elicited a deep inner conflict towards one's physical reality. Moreover, this “phallocentric” obsession was only corroborated by the scientific literature of the time which “advanced theories that the larger genitalia coincided with a smaller brain, lower intellectual endowment, and increased lasciviousness.”29

Knowing all this, can we read the Cleaver Sleeves as a protruding middle finger to — in his own words — “four hundred years minus my balls”30? Materialising Cleaver’s “insurrectionary act” against the power of white men over black bodies.”31Replacing Black pain with Black pleasure. “We shall have our manhood,” he said, “we shall have our manhood or the earth will be levelled by our attempts to gain it.”32

Supporting this idea, In The Psychology of Clothes, Flugel says that “in young children, the pleasure in decoration develops earlier than the feeling of shame in exposure”33 and by making his point not to “tuck it behind the pants”34 Cleaver makes the personal (his body) political. Rejecting the history heaped on him by America’s colonial past. This is hardly surprising when considering that the body was the only currency African American men had during slavery. In Slaves to Fashion by Monica L. Miller, she identifies that “from the arrival of the first African slaves on American soil, the discourse in race, the definitions and meanings of blackness, have been intricately linked to issues of theatre and performance.”35 Fascinatingly, there are many examples of slaves said to have been “addicted to dress.” Those who “stole better clothing” could “pass more easily for freemen and enter the market as consumers.”36 In this sense, self-styling transgressed itself and became a practical, necessary survival tool. Performing freedom by convincingly wearing clothes beyond your means often equated to freedom. It remains true that “African Americans have historically spent a greater portion of their income on clothing and dress than white Americans.”37

Stuart Hall puts the idea of African American self-fashioning beautifully in his essay What Is This “Black” in Black Popular Culture? that “within the black repertoire, style — which mainstream cultural critics often believe to be the mere husk, the wrapping, the sugar coating on the pill — has become itself the subject of what is going on…think of how these cultures have used the body — as if it was, and often it was, the only cultural capital we had. We have worked on ourselves as the canvases of representation.”38

Looking then at style as powerful “cultural capital,” the Black Panther Party is a brilliant example of how clothes can draw an audience in to participate with a political agenda. The party’s uniform of black leather and traditional African accessorising was a loaded style that contributed massively to the dissemination of their work. Both with leather’s history of subversive associations and as the modern incarnation of skinning and decorating oneself with “the kill”. Elementally, wearing black leather is wearing an additional black skin. And interestingly, at the fashion show debut of his Cleaver Sleeves, Cleaver told the San Francisco Examiner that “(the medieval codpiece) was for protection. Mine is conceived more as a second skin.”39 Perhaps then, the jeans are an attempt to bridge the gap between Cleaver’s humanity and materiality, irrespective of the limitations of fabric.

In that same article, it concludes that the Cleaver Sleeves “make a sex object of men in exactly the way that low-cut dresses have made sex objects out of women.”40 I’d argue the Cleaver Sleeves are more sexually loaded than “low-cut dresses” with skin on display because the reality of seeing skin demystifies its sexual association. While alluding to it through a material “second skin” works only to further the distance between flesh and fantasy — fuelling the intrigue and eroticisation of what it’s working to conceal.

There is an inherent shame in Cleaver’s use of material to allude to but ultimately conceal the crux of his argument. As art critic Michael Glover said on codpieces, “their faux cod-phallus, crispy and hard on the surface yet so yielding at its centre”41 reveals their irony and weakens the authority of their design. This supports what Flugel believed to be “the essential opposition” of dress, an inherent navigation “between the two motives of decoration and modesty.”42

Maybe the ideal solution for Cleaver would have be one where men didn’t have to wear jeans at all. At the aforementioned meeting with Harvard undergraduates he said, “it's amazing now to think that thousands of years ago, men were walking around with no clothes on, and thought nothing of it. Now men walk around with clothes on and think nothing of it. What a shock it must have been then, to see the first person wear clothes!”43 Perhaps then, any attempt to strike a middle ground between pre-clothes freedom and America’s puritanical colonial roots was just too irreconcilable to work on a pair of jeans.

Altogether, the Cleaver Sleeves elicit layered interpretations. Yet ultimately their contribution to material culture was too confrontational, or in Cleaver’s mind, revolutionary, at a time when unisex fashion and the peace movements dominated. Disarmament was the opposite look of penis-positive jeans. And beyond context, it remains just too ironic for a convicted rapist to have convincingly assuaged men into adopting phallic-forward fashion.

The “regime of the penis”44 was over, least of all to be reintroduced by a man whose body had been both literally and psychically enslaved to the objectifying stereotype that doomed these jeans to failure.

The Cleaver Sleeve Jeans

A close up of the “Portrait of Antonio Navagero” by Giovanni Battista Moroni, Italy, 1565. Illustrating the codpiece’s decorative virility by the early 16th century. Via The Guardian

Maroon denim pants by Eldridge Cleaver Unlimited, circa 1975. Via Boo Hooray Archive

Mamie Till Mobley weeping at her son’s funeral in Chicago, 1955. Emmet Till, 14, was kidnapped, beaten and killed, hours after being accused of whistling at a white woman. Photo: David Jackson via AP

Black Panther Party, Photographer Unknown, circa 1967. Via The Kansas City Defender

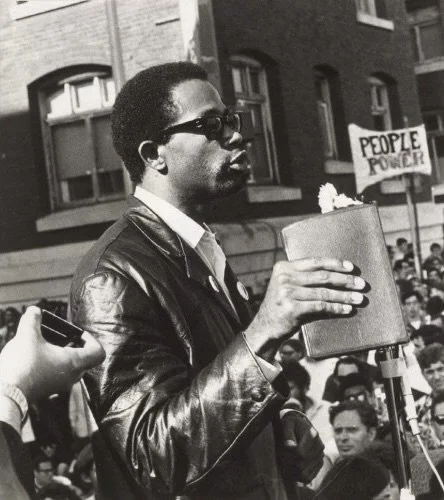

Eldridge Cleaver, Paris, 1975. Photo: René Burri via Magnum Photos

Eldridge Cleaver Unlimited clothing label, 1975. Via Between the Covers Rare Books.

“Memory Mistake of the Eldridge Cleaver Pants”, a reconstruction of an Eldridge Cleaver Unlimited design, Paul McCarthy, Los Angeles, 2008.

A wedding party with bridesmaids on Fifth Ave in Harlem, 1983, New York. Photo: Thomas Hoepker via Magnum Photos

Black Panther Party, Photographer Unknown, circa 1967. Via The Kansas City Defender

Advert for Eldridge Cleaver's Trousers, Source and Date Unknown. Via UAL Research Online.

Eldridge Cleaver, 1968. Photo: Stephen Shames via National Portrait Gallery

1 On April 6th 1968, Cleaver was involved in a shootout with the Oakland Police Department. Black Panther Party member Bobby Hutton died whilst Eldridge Cleaver and two police officers were injured. According to Kathleen Cleaver, Eldridge’s ex-wife, the decision to confront the police came from Cleaver in response to Martin Luther King’s assasination two days earlier. Hutton was unarmed, partially nude and surrendering. Most reports agree that Hutton was shot at least ten times. His death catapulted the Panthers into a national organization.

2 Horacio, Silva. “Radical Chic”. New York Times Magazine, 23 Sept. 2001. https://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/23/magazine/radical-chic.html

3 Dauphin, Gary. “The Cleaver Sleeve”. Objects, Summer 2008. https://www.bidoun.org/articles/the-cleaver-sleeve

4 Stillman, Mark. “Eldridge Cleaver’s New Pants”. The Harvard Crimson, 26 Sept. 1975. https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1975/9/26/eldridge-cleavers-new-pants-peldridge-cleavers/

5 Johnson, Charles. “A Soul’s Jagged Arc”. The New York Times, 3 Jan. 1999. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1999/01/03/issue.html

6 Attfield, Judy. “The Body: The Threshold Between Nature and Culture” Wild Things The Material Culture of Everyday Life, Berg, 2000.

7 Glover, Michael. Thrust: A Spasmodic Pictorial History of the Codpiece in Art, David Zwirner Books, 2019.

8 Fisher, Will. “‘That codpiece ago’: codpieces and masculinity”. Materializing Gender in Early Modern English Literature and Culture, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

9 Howard, Jean and Rackin, Phyllis. Engendering a Nation: A Feminist Account of Shakespeare’s English Histories, New York: Routledge, 1997.

10 Fisher, Will. Materializing Gender in Early Modern English Literature and Culture, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

11 Fisher, Will. Materializing Gender in Early Modern English Literature and Culture, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

12 Fisher, Will. Materializing Gender in Early Modern English Literature and Culture, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

13 Fisher, Will. Materializing Gender in Early Modern English Literature and Culture, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

14 Kifner, John. “Eldridge Cleaver, Black Panther Who Became G.O.P. Conservative, Is Dead at 62”. The New York Times, 2 May 1998. https://www.nytimes.com/1998/05/02/us/eldridge-cleaver-black-panther-who-became-gop-conservative-is dead-at-62.html

15 Kifner, John. “Eldridge Cleaver, Black Panther Who Became G.O.P. Conservative, Is Dead at 62”. The New York Times, 2 May 1998. https://www.nytimes.com/1998/05/02/us/eldridge-cleaver-black-panther-who-became-gop-conservative-is dead-at-62.html

16 Johnson, Charles. “A Soul’s Jagged Arc”. The New York Times, 3 Jan. 1999. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1999/01/03/627259.html?pageNumber=256

17 Stillman, Mark. “Eldridge Cleaver’s New Pants”. The Harvard Crimson, 26 Sept. 1975.

18 Phillips, John. The Marquis De Sade, A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, 2005.

19 Stillman, Mark. “Eldridge Cleaver’s New Pants”. The Harvard Crimson, 26 Sept. 1975. https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1975/9/26/eldridge-cleavers-new-pants-peldridge-cleavers/

20 Johnson, Charles. “A Soul’s Jagged Arc”. The New York Times, 3 Jan. 1999. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1999/01/03/627259.html?pageNumber=256

21 Stillman, Mark. “Eldridge Cleaver’s New Pants”. The Harvard Crimson, 26 Sept. 1975. https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1975/9/26/eldridge-cleavers-new-pants-peldridge-cleavers/

22 Seale, Bobby. “Eulogy: Eldridge Cleaver”. TIME Magazine, 11 May. 1998. https://time.com/archive/6732761/eulogy-eldridge-cleaver/

23 Richeson, Marques P. “Sex, Drugs, and…Race-to-Castrate: A Black Box Warning of Chemical Castration’s Potential Racial Side Effects”. Harvard Black Letter Law Journal, 2009.

24 Richeson, Marques P. “Sex, Drugs, and…Race-to-Castrate: A Black Box Warning of Chemical Castration’s Potential Racial Side Effects”. Harvard Black Letter Law Journal, 2009.

25 Richeson, Marques P. “Sex, Drugs, and…Race-to-Castrate: A Black Box Warning of Chemical Castration’s Potential Racial Side Effects”. Harvard Black Letter Law Journal, 2009.

26 Richeson, Marques P. “Sex, Drugs, and…Race-to-Castrate: A Black Box Warning of Chemical Castration’s Potential Racial Side Effects”. Harvard Black Letter Law Journal, 2009.

27 Blake, Art. “Re-Dressing Race and Gender: The Performance and Politics of Eldridge Cleaver's Pants”. Fashion Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2018. https://www.fashionstudies.ca/re-dressing-race-and-gender

28 Richeson, Marques P. “Sex, Drugs, and…Race-to-Castrate: A Black Box Warning of Chemical Castration’s Potential Racial Side Effects”. Harvard Black Letter Law Journal, 2009. https://journals.law.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/92/2012/11/95-132.pdf

29 Richeson, Marques P. “Sex, Drugs, and…Race-to-Castrate: A Black Box Warning of Chemical Castration’s Potential Racial Side Effects”. Harvard Black Letter Law Journal, 2009.

30 Sexton, Jared. “Race, Sexuality, and Political Struggle: Reading Soul on Ice”. War, Dissent, and Justice: A Dialogue, Vol 30, Issue 2, 2003, JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/29768182?read-now=1&seq=8#page_scan_tab_contents

31 Blake, Art. “Re-Dressing Race and Gender: The Performance and Politics of Eldridge Cleaver's Pants”. Fashion Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2018. https://www.fashionstudies.ca/re-dressing-race-and-gender

32 Vandiver, Josh. “Plato in Folsom Prison: Eldridge Cleaver, Black Power, Queer Classicism”. Political Theory, Vol. 30, December 2016. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26419438

33 Flugel, J C. The Psychology of Clothes, Hogarth Press and The Institute of Psychoanalysis, 1950.

34 Stillman, Mark. “Eldridge Cleaver’s New Pants”. The Harvard Crimson, 26 Sept. 1975. https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1975/9/26/eldridge-cleavers-new-pants-peldridge-cleavers/

35 Miller, Monica L. “Introduction”. Slaves to Fashion, Black Dandyism and The Styling of Black Diasporic Identity, Duke University Press, 2009.

36 Miller, Monica L. “Crimes of Fashion: Dressing the Part from Slavery to Freedom”. Slaves to Fashion, Black Dandyism and The Styling of Black Diasporic Identity, Duke University Press, 2009.

37 Miller, Monica L. “Crimes of Fashion: Dressing the Part from Slavery to Freedom”. Slaves to Fashion, Black Dandyism and The Styling of Black Diasporic Identity, Duke University Press, 2009.

38 Miller, Monica L. “Introduction”. Slaves to Fashion, Black Dandyism and The Styling of Black Diasporic Identity, Duke University Press, 2009.

39 Unknown. “Eldridge Cleaver show off his male liberation front”. The San Francisco Examiner, 15th Aug. 1975. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-san-francisco-examiner-cleaver-pant/23727100/?locale=en-GB

40 Unknown. “Eldridge Cleaver show off his male liberation front”. The San Francisco Examiner, 15th Aug. 1975. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-san-francisco-examiner-cleaver-pant/23727100/?locale=en-GB

41 Stillman, Mark. “Eldridge Cleaver’s New Pants”. The Harvard Crimson, 26 Sept. 1975. https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1975/9/26/eldridge-cleavers-new-pants-peldridge-cleavers/

42 Flugel, J C. The Psychology of Clothes, Hogarth Press and The Institute of Psychoanalysis, 1950.

43 Stillman, Mark. “Eldridge Cleaver’s New Pants”. The Harvard Crimson, 26 Sept. 1975. https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1975/9/26/eldridge-cleavers-new-pants-peldridge-cleavers/

44 Fisher, Will. Materializing Gender in Early Modern English Literature and Culture, Cambridge University Press, 2006.